Burchard’s Box and the Birth of the Census

In contrast to antiquity’s most infamous box, namely the one Pandora dared to open, the box we found at the Photographic Collection of the Warburg Institute in London did not contain all that is evil and vicious. Quite the opposite as it even confronted us with Apollo, God of light, wisdom and the arts. While gods usually do not reside in wooden boxes, Apollo’s presence here would echo through decades of research in the fields of art history and archaeology.

The box, currently located in the Photographic Collection of the Warburg Institute, contains many cards and notes written in the hands of the art historians Ludwig Burchard (1886–1960) and Alfred Scharf (1900–1965), German Jewish scholars who had fled national socialist Germany. Burchard was a renowned specialist on the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens. He reached London in 1935 and there was able to continue his life-long project of gathering documentation on Rubens. Eventually, Burchard’s work would form the core of the Rubineaum research institute in Antwerp.

In the 1940s, one focus of Burchard’s interests was the question of which antiquities could have been known to Rubens and his contemporaries. He was able to employ Scharf to research the topic at the Warburg Institute. At Burchard’s direction, Scharf compiled index cards documenting the antiquities known to Rubens and other artists in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. He headed these cards with the name of a particular antique monument, writing below a list of works by Rubens and other artists that responded to it.

Among the cards in Burchard’s box is one dedicated to the Apollo Belvedere. The cards and notes related to the statue are illustrated and transcribed below.

Burchard Census, Warburg Institute Photographic Collection

Ludwig Burchard, © Collectie Stad Antwerpen

Alfred Scharf, © Estate of Alfred Scharf, by kind permission of Ursula Price

Notes on the Apollo Belvedere

The cards and notes included facts about the monument and its postclassical history: its findspot, provenance and restorations, along with sixteenth- and seventeenth-century artistic representations that responded to it, like those illustrated to the right, by Albrecht Dürer, and below, by Rubens. In this manner the structure of Burchard’s index cards closely resemble that of the index cards developed for the Census by Phyllis Bober and her collaborators, which is the focus of Room 2.

The work of Burchard and Scharf directly inspired the methodology of the Census and established a model for the project’s collaborative nature, as is visually displayed by Burchard’s notes attached to Scharf’s cards.

Images: Apollo Belvedere, © bpk Bildagentur/Scala; Albrecht Dürer, Apollo and Diana, © The Trustees of the British Museum; Peter Paul Rubens, The Council of the Gods, © bpk / RMN — Grand Palais / Hervé Lewandowski / Christian Jean

The Birth of the Census

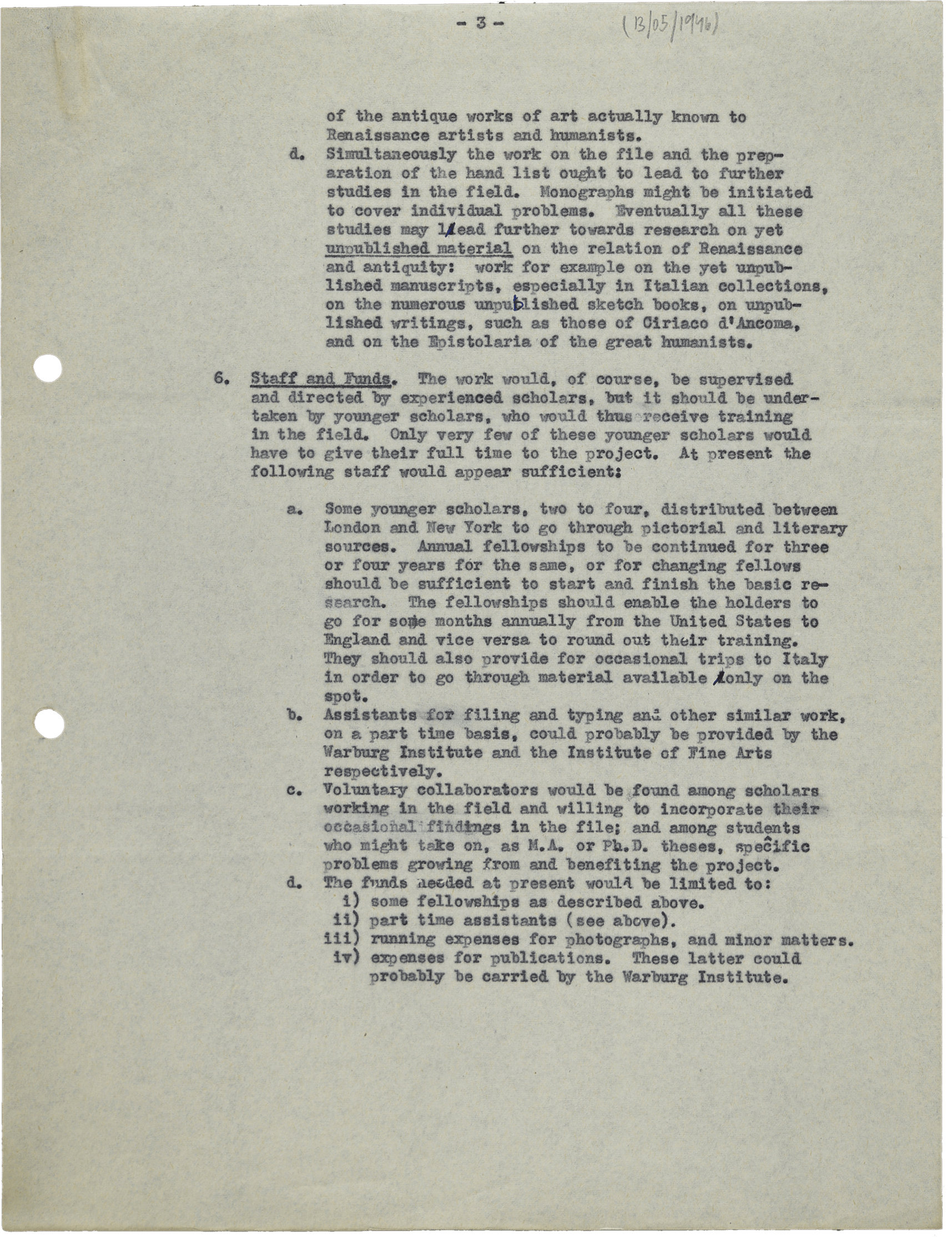

The Census was born just as the Second World War came to a close. The need for such a tool was first expressed by Richard Krautheimer (1897–1994), a German art historian who had fled to the US to escape Nazi persecution. Since 1937, Krautheimer had taught at Vassar College, while also lecturing at New York University.

In the 1940s, Krautheimer was working on a series of volumes on early Christian basilicas, the Corpus Basilicarum Christianarum Romae. Together with his wife, Trude Krautheimer-Hess, he was also writing a monograph on the Florentine Renaissance sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti. Frustrated by a lack of specific knowledge on 15th-century knowledge of antique art, in September, 1945 he wrote to the Director of the Warburg Institute in London, Fritz Saxl, with the suggestion that they begin to organise a ‘Corpus’ of antiquities known to the 15th century. Saxl enthusiastically replied that he would like to collaborate on such a project and immediately cited the index cards begun by Burchard and Scharf as a model:

I tried to instruct myself somewhat on questions of early 15th century knowledge of antique art. But, as you know, the difficulties are really enormous. […] Couldn’t we try to organize a corpus of antiques known to the 15th century? I wish we could discuss it when you come here this winter.

What you say about the 15th century collections of antiques is very true. Scharf has for years collected the material, at my suggestion. […] He reconstructed i.a. the earliest 15th century sketchbooks from the antique. It is time that somebody, either at New York University or with us, tackled the subject.

Below are photographs and transcriptions of this exchange of letters, which can be considered the origin of the Census project. They are housed in the Warburg Institute Archive in London.

Richard Krautheimer, © Archives and Special Collections, Vassar College

Fritz Saxl, c. 1939, © Warburg Institute Archive

Developing a Format

When Fritz Saxl was visiting the USA in 1946, he and Krautheimer developed their ideas for a Census of Antiquities known to the Renaissance. They agreed that Saxl would request initial funding for the project from Henry Allen Moe of the Guggenheim Foundation. On 13 May 1946, in preparation for this meeting, Krautheimer sent Saxl an outline for the Census project, detailing its format, contents, working processes and funding.

Here Krautheimer points out that further ‘information regarding the antique material accessible to Renaissance scholars and artists’ is urgently needed to achieve a more ‘thorough and more specific understanding of the phenomenon of the Renaissance’. The value of the Census project would lie in clarifying the history of early finds and collections, the history of taste, and the impact of antiquity generally on Renaissance art, art theory, and humanistic studies. He advises that the project’s scope should be limited to Italy and should cover the ‘period up to 1532’ [sic], or possibly only up to 1490’.

The Warburg Institute would supervise the collection of literary sources, while the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU would take responsibility for the pictorial sources and the history of antique works of art.

The full content of Krautheimer’s letter to Saxl, also housed in the Warburg Archive, is illustrated and transcribed below.

Three types of sources referring to or describing antique works of art extant in the Renaissance are available for such a Census.

Literary sources of the Renaissance (Inventories of collections; travel descriptions; letters of humanists; writings on art and on antiquity).

Pictorial sources of the Renaissance

-

- reproductions of antique works (sketches; books; individual drawings; engravings).

- works of art inspired or dependent on antique prototypes (paintings, sculpture, engravings, medals, etc.)

Remnants of antiquity having survived through the Middle Ages and Renaissance to this date. (Collections of sarcophagi at Salerno; Florence; Pisa; Arles; sculpture at Rome.)

Other letters in the Warburg Institute Archive detail the founders’ hopes for collaborators on the project. A plan which eventually fell through was to have Roberto Weiss, Lecturer in Italian at University College London, collect the textual sources. They note that the German art historian William S. Heckscher would spend a year at the Institute for Advanced Studies at Princeton working on antiquities in Rome during the Renaissance.

Letters reveal that at this early stage of the project, the creators of the Census were grappling with concerns voiced in particular by ‘Lee, Pan and Kennedy’ [Rensselaer Lee, Erwin Panofsky and Clarence Kennedy] that the format may be too sterile. Reference was made to the ’spectre of the Christian Index’, that is, the card system of the Index of Christian Art founded at Princeton in 1917. On the 8th of October, Krautheimer addressed these concerns to Saxl, writing that ‘an index is as good and as sterile as the people who make and use it’. He suggested that they could revise the plan, ‘placing more emphasis on individual studies which would centre around the main problem and making the index a mere offshoot of such studies’. A shift towards collecting materials by means of individual research projects would ‘give more freedom to the individual but at the same time it may, I fear, postpone the publication of a handlist’.

In the passage cited on the right, Krautheimer then shared thoughts on the chronological scope of the project that echo through the history of the Census project, up to the present day. Seventy-five years later its focus remains on the Renaissance response to genuinely antique monuments, rather than Renaissance inventions inspired by the antique, and on the period 1400–1600.

The letter of 8 October, 1946 is an essential document for the history of the Census. In it Krautheimer also expresses his support of Saxl’s proposal to have ‘Mrs. Bober’, the American archaeologist Phyllis Bober, survey periodicals and gather literature for the Census, as is discussed in Room 2.

There also have been several suggestions concerning the field to be covered in our project. One is to extend the field of research so as to include practically the entire XVII century. I am quite strongly opposed to this, because the material would grow without limits, and I am sure that the two of us (and I might add, Lehmann whom I saw yesterday) will agree. Another suggestion is to include the case history of Antiques known during the Middle Ages. This suggestion seems to be valid. A third suggestion was to include derivations from Antiquity in Renaissance paintings (postures, etc,), but that would overlap with the Warburg Atlas and definitely lead in a different direction.

Burchard's Box and the Birth of the Census is a collaborative exhibition by:

Christopher Lu (Warburg Institute)

Lucy Salmon (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin)

Zahra Syed (Warburg Institute)

Hannah Sommer (Humboldt-Univeristät zu Berlin)