Bober and Rubinstein: Index Cards and Photographs

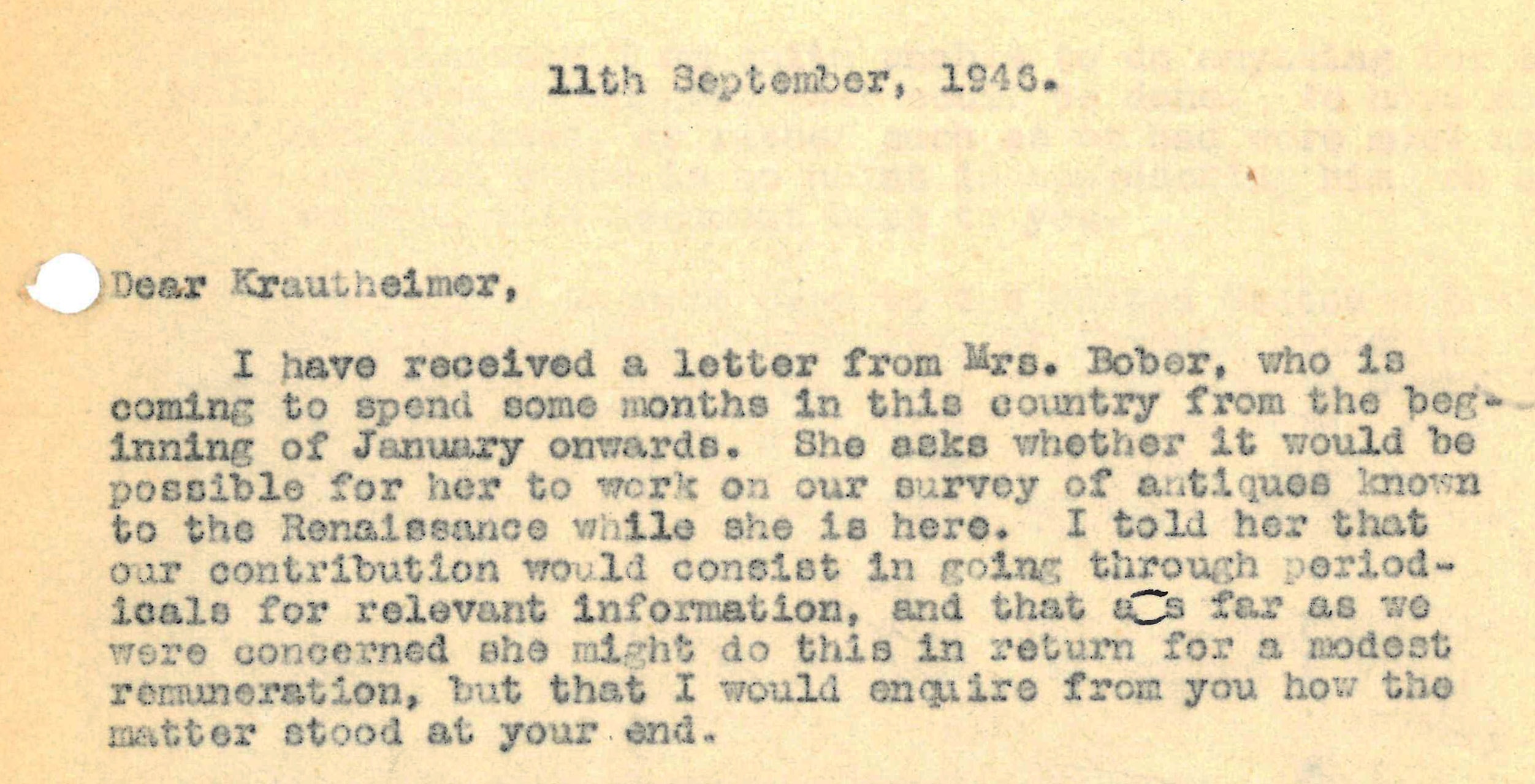

In a letter of September 11, 1946, Saxl informed Krautheimer that ‘Mrs. Bober’ would like to work on their survey of antiques. In 1947, Phyllis Pray Bober, who had recently received her PhD in archaeology from NYU, joined the project, initially with the role of collecting bibliography.

Although Saxl’s premature death in 1948 was a significant setback, the Census project entered a more established phase in 1953, when NYU became a partner institution together with the Warburg Institute. From 1953 to 1973, as Research Associate and eventually as founding chair of the Department of Fine Arts, Bober received institutional support from NYU for her work on the Census.

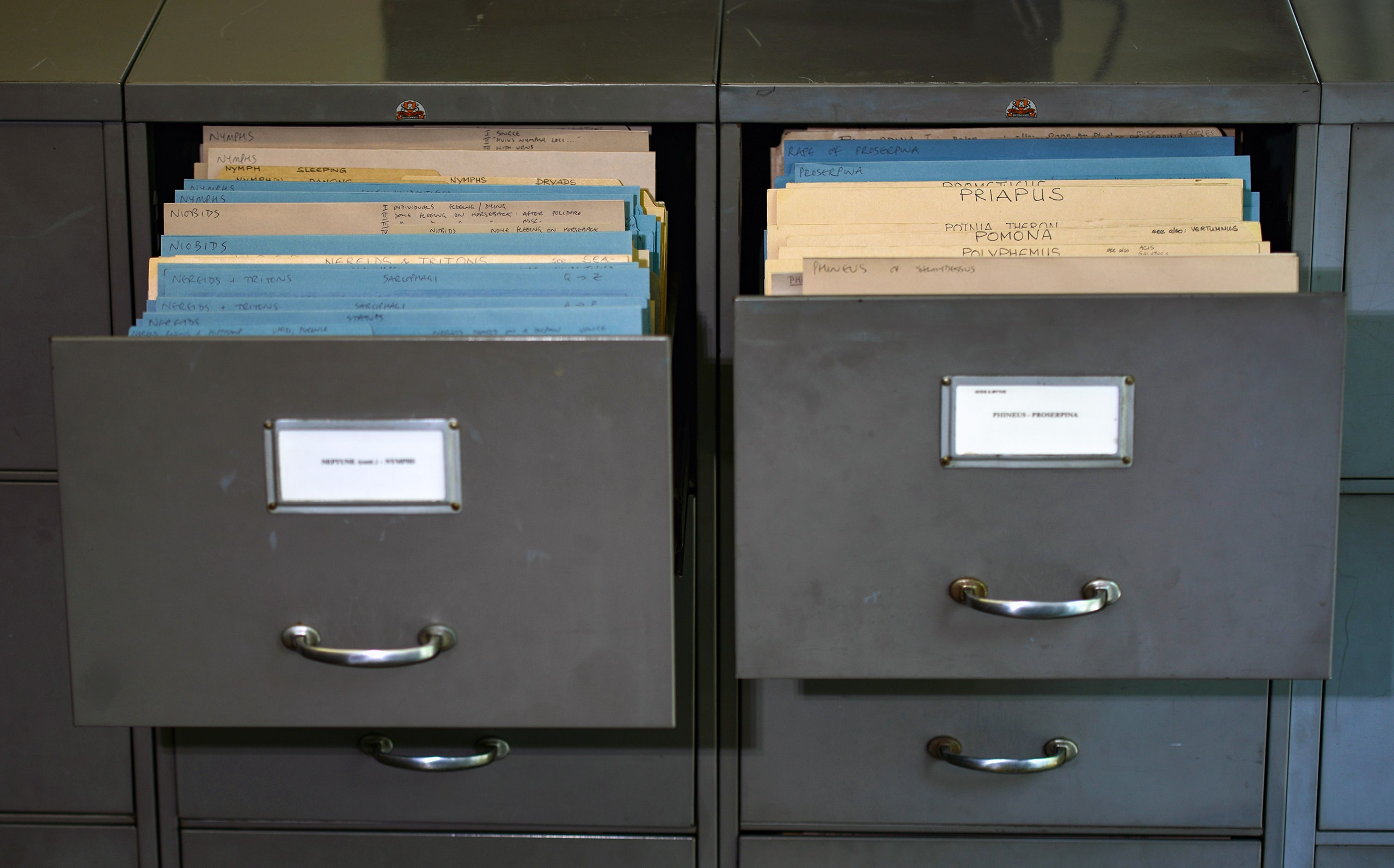

Under Bober’s direction, and in collaboration with the Photographic Collection at the Warburg Institute, its records expanded.

In the early phase of the project, particular emphasis was placed on the study of Renaissance sketchbooks, and their publication in the Studies of the Warburg Institute series. Bober’s own publication of the sketchbooks of the Bolognese artist Amico Aspertini appeared in this series in 1957. Identifying Renaissance drawings after the antique continued to be an important part of Bober’s work on the Census, and NYU would occasionally subsidise summer research trips to Europe, where she would search drawings collections for new discoveries. In 1972, Bober left NYU and became a Dean and Professor at Bryn Mawr. At Bryn Mawr she could explore her passion for the history of cookbooks and cuisine, culminating in the publication of Art, Culture and Cuisine: Ancient and Medieval Gastronomy in 1999.

A brief timeline of Bober’s career is found below.

Warburg Institute Archive, GC, Fritz Saxl to Richard Kratuheimer, 11.9.1946

Bober’s work on the Census involved collaboration with the Warburg Institute across the Atlantic. She would compile index cards in the US and then send copies of them in batches to London, where curators in the Photographic Collection would assemble images of the ancient monuments and relevant Renaissance works of art.

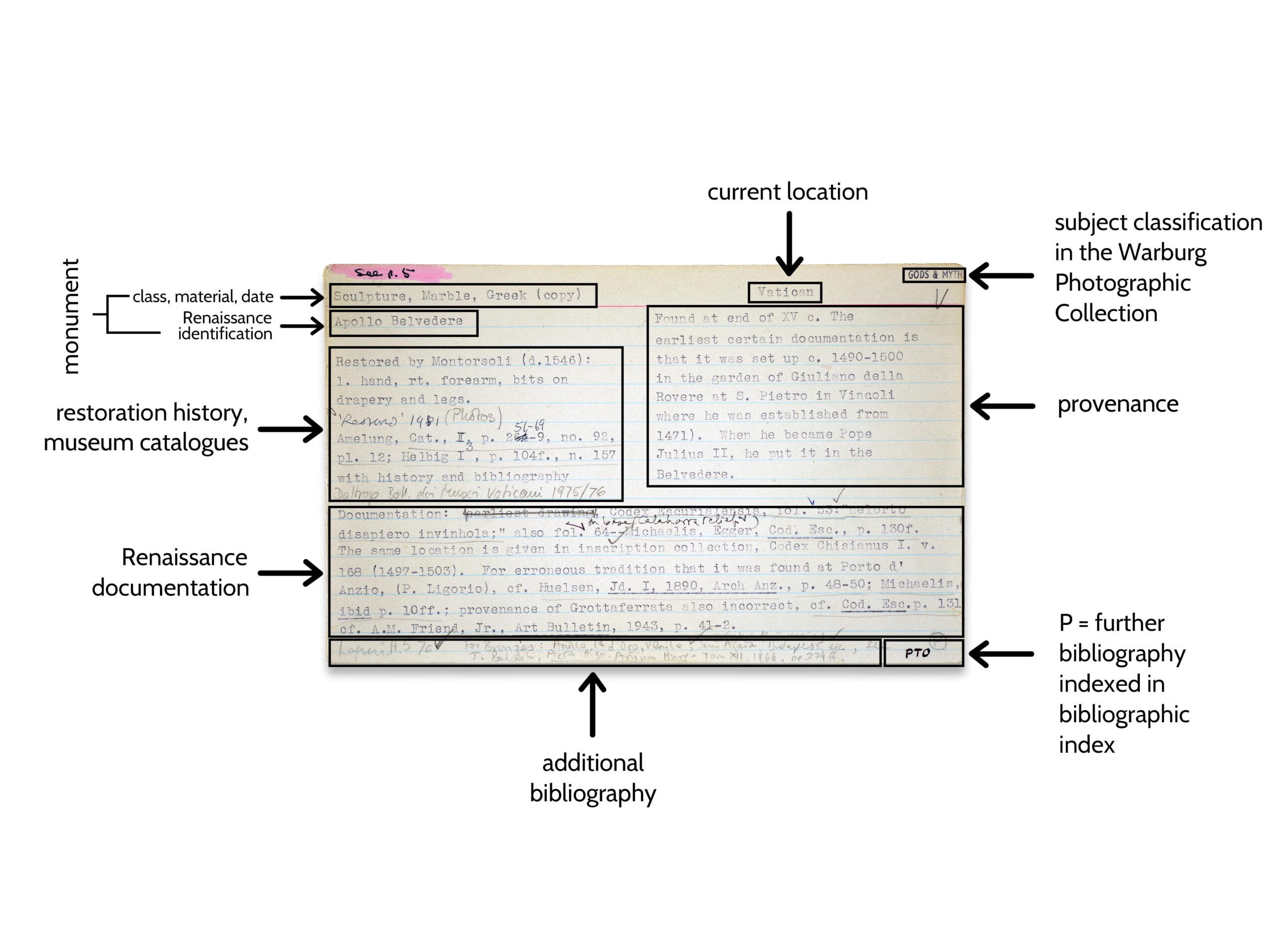

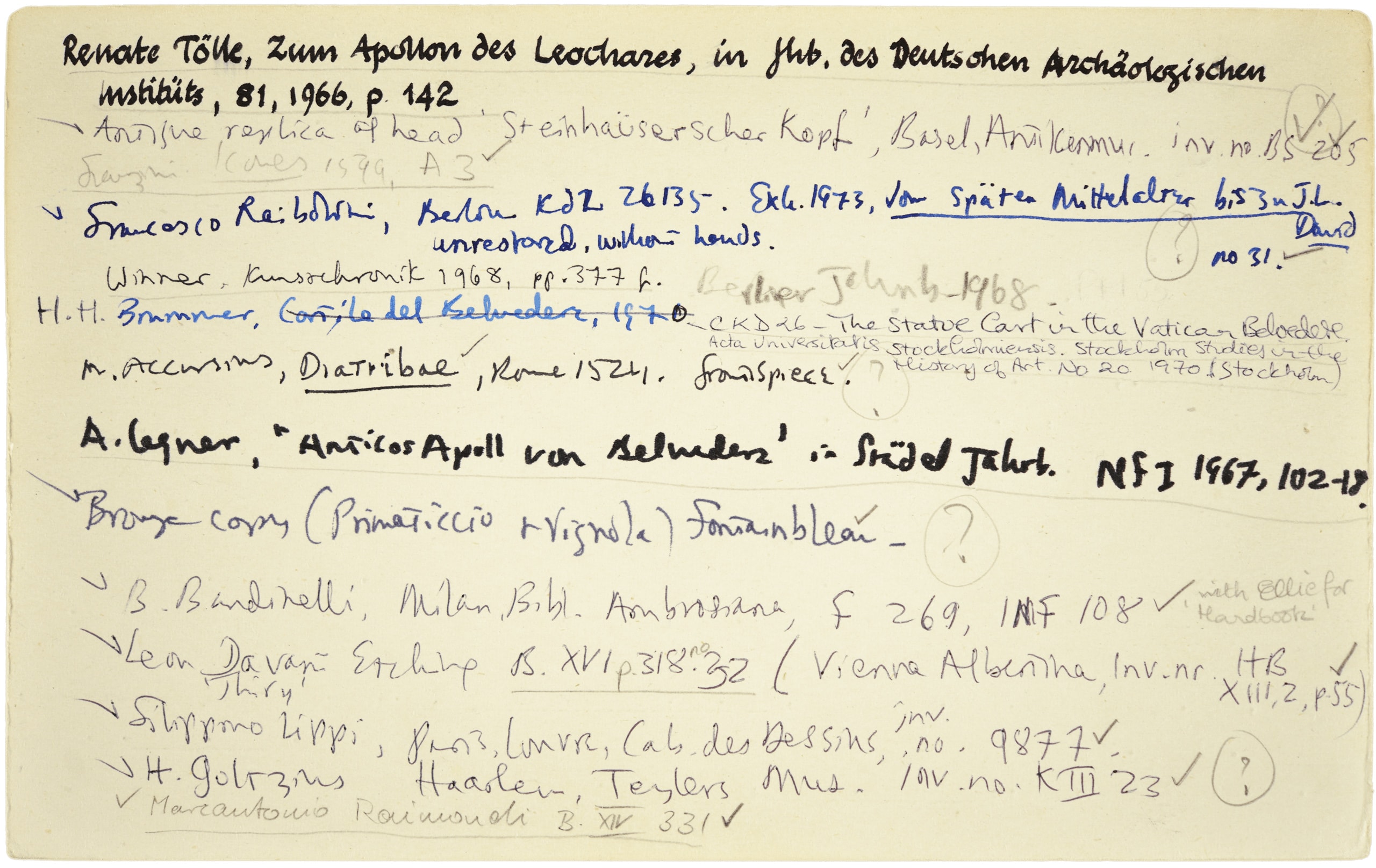

The front of the Apollo Belvedere Census card, Warburg Institute Photographic Collection

Cabinets in the Photographic Collection of the Warburg Institute with blue Census Folders

A copy of each photograph ordered in London was also sent to the Institute of Fine Arts in New York to accompany the index cards kept there. In this manner, the Census grew in duplicate, and could be accessed in both partner institutions. The London copy of the Census remains at the Warburg Institute, while in 1995 the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University donated their copy of the Census to the Institut für Kunst- und Bildgeschichte in Berlin.

The ‘analogue’ Census built up by these duplicate sets of index cards and photographs adheres to Krautheimer’s initial outline of the project. From the beginning, the Census was aimed at documenting ‘specific information regarding the antique material accessible to Renaissance scholars and artists’ (See Room 1, Krautheimer, Letter to Saxl of 13.5.46, fol. 2). Bober’s index cards maintain this focus: antique monuments provide the heading for each card, with information given on its current location, provenance, and restoration history. Underneath, the cards list literary and visual sources from the Renaissance (such as sketchbooks and prints), as well as bibliographic references. Renaissance all’antica inventions, forgeries or fantasy conceptions of the antique were not included on the cards. As Bober wrote in 1963, ‘I do not concern myself with seeking out individual poses in, let us say, Renaissance paintings, because artists may either arrive at these independently or reactivate an ultimately classical prototype transmitted in medieval guise. It is rather the testimony of direct copying or adaptation, of groups of figures or complete compositions, which has reliable documentary value for the Census’, (Bober 1963, p. 85). The Census project long relied on Bober’s archaeological expertise to fulfil the original goal, that is, to replace a vague understanding of antique ‘influence’ with an accurate and specific understanding of the antique monuments known in the Renaissance.

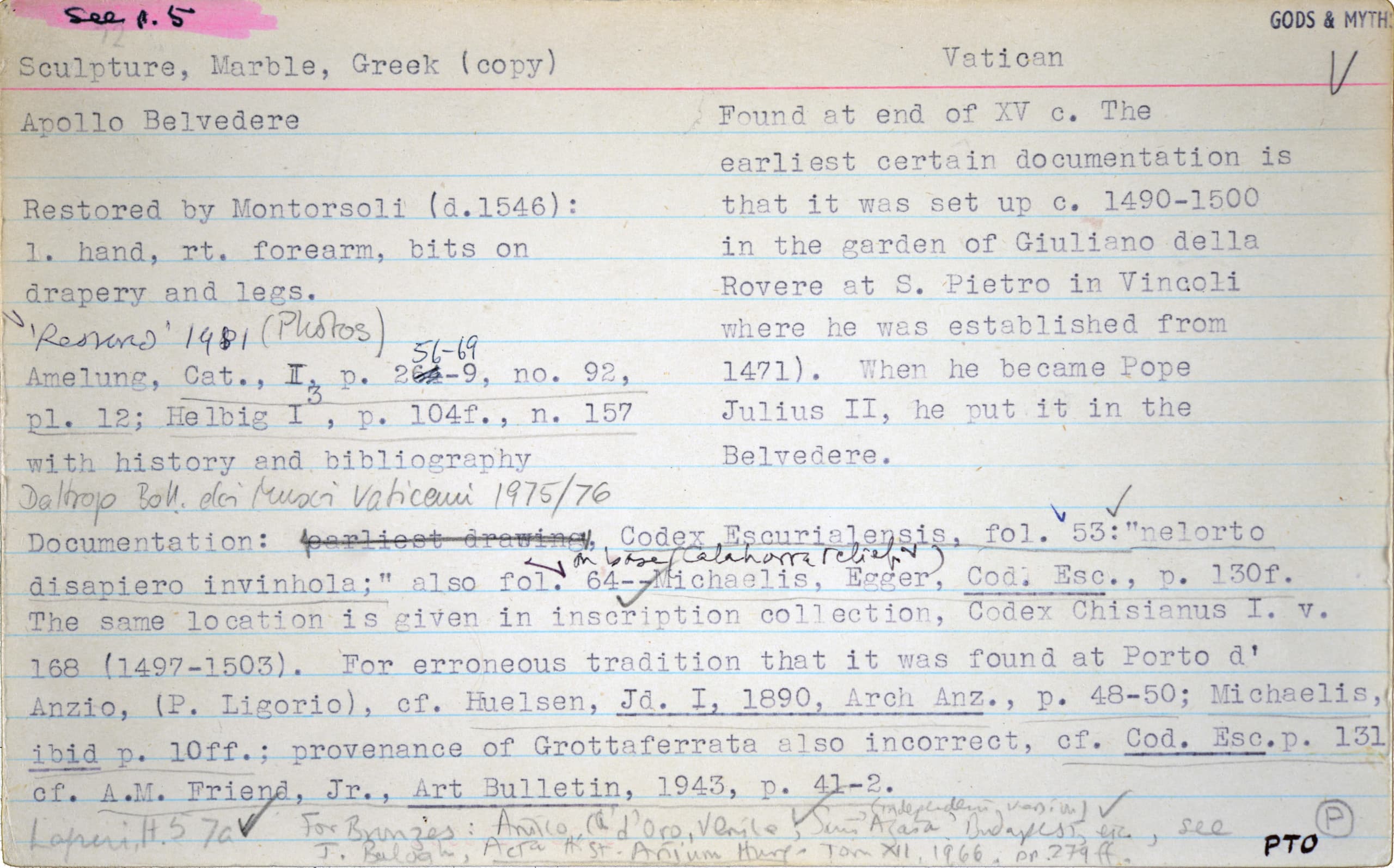

Below, one can see how the index card for the Apollo Belvedere—from the Warburg Institute’s copy of the Census—was organised. In this example, Bober’s typed card made in New York was completed in London with handwritten notes, mostly by Ruth Rubinstein. Rubinstein’s check marks on the card confirm the presence of the relevant photographs in the Warburg’s Photographic Collection.

Illustration, research, organization, and expansion were part of Ruth Rubinstein’s work at the Census photographic collection. After receiving Bober’s typed index cards with descriptions of antique monuments, Rubinstein sourced the illustrative material. From 1957 until 1996, Rubinstein held the role of special research assistant for the Census, searching the photo collection for relevant photographs, ordering those that were missing and organising them in the collection’s existing index. The Census photos were in this manner integrated into the iconographic classification system of the Warburg Institute’s photo collection, but kept in recognisably bright blue folders. Every time she located a photograph, Rubinstein put a check mark on the card. When she discovered further representations of the antique monument, she noted them by hand. The backs of the Census cards and photographs in London are filled with Rubinstein’s ’scribbles’: Renaissance sources discovered in books and auction catalogues, or collected during her daily interactions with visitors to the Photographic Collection. The students in the Census seminar were able to speak to several of Rubinstein’s former colleagues, who remembered how her warm and welcoming personality drew many academics to the Census. The project grew through Rubinstein’s wide circle of contacts and friends, and in the social gatherings at the home of Ruth and Nicolai Rubinstein in Hampstead. Below are selected excerpts from an unpublished typescript in the Warburg Institute Archives of Ruth Rubinstein’s talk, ‘My Thirty-Five Years at the Census in Ten Minutes’. Rubinstein delivered it at a Census Colloquium at the Warburg Institute held in March 1992.

Ruth Rubinstein, © Warburg Institute Archive

The back of the Apollo Belvedere Census card, Warburg Institute Photographic Collection

Since that meeting in Rome, the cut-off date of the Census had been extended from 1527 to 1550, and now to 1600, resulting in mysterious crowds of draped female statues waiting to be identified and to enter the Census.

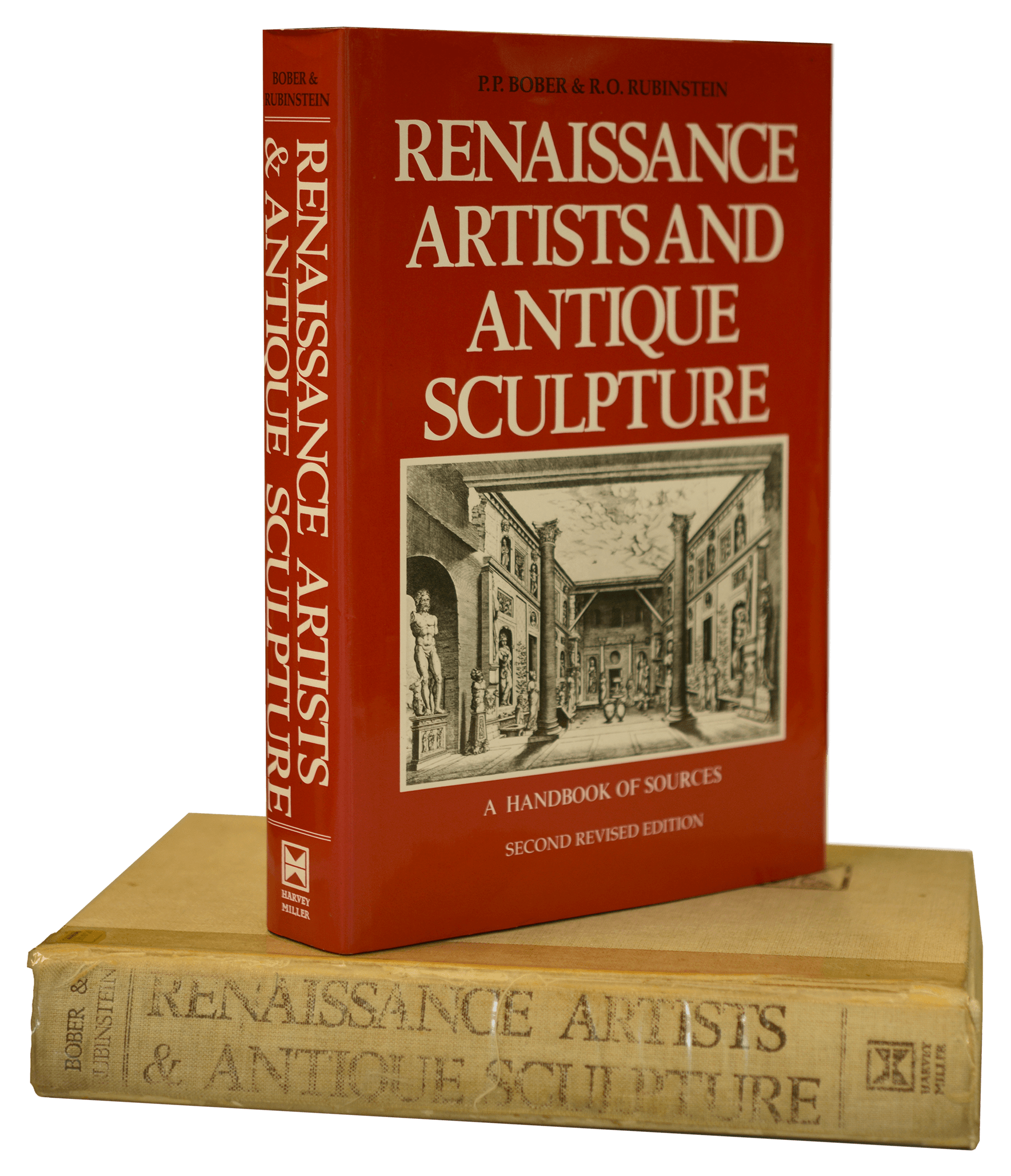

In 1986, Bober and Rubinstein published Renaissance Artists and Antique Sculpture: A Handbook of Sources, a co-authored text with contributions by the archaeologist Susan Woodford. The book combined descriptions of the antique reliefs, sarcophagi and sculptures considered the most important for Renaissance artists with lists of visual sources and updated bibliography. The text consolidated decades of research and reflects the Census’s long-term focus on Renaissance figurative sketchbooks. Pre-dating the dissemination of a computerised version of the Census on CD-Rom, it made the results of the project widely available for the first time. It quickly became a standard reference work and in 2011 was reissued in a revised edition.

The fact that the title of the book prioritises Renaissance artists reflects a shift in Bober’s approach to the Census project. As she would write in 1989, ‘from today’s perspective, I must confess that at the beginning of work for the Census I was all archaeologist’. Eventually she became ‘a historian of Renaissance art as much as an archaeologist’ (Bober 1989, p. 375). Bober’s fertile imagination was increasingly stimulated by Renaissance visual art and cultural history, as is seen in the publication in 1977 of what would become a classic article, ‘The Coryciana and the Nymph Corycia’ (Bober 1977). This study in the Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes explored the theme of the sleeping Nymph in the artistic, poetic and antiquarian circles of 15th- and 16th-century Rome.

‘Bober and Rubinstein: Index Cards and Photographs’ (Room 2) and ‘Phyllis Bober and the Census Digitisation’ (Room 3) are collaborative exhibitions by:

Ariana Binzer

Ioana Dumitrescu

Marie Erfurt

Friedrich Fetzer

Marina Goldinstein

Helene Hellmich

Ayami Mori

X. Tuan Pham

Leetice Posa

Claire-Elisa Rüffer

Antonia Rosso

Lidia Strauch

Elisa Tinterri

Radu Vasilache

Kevin Varela

Bahar Yerushan

Zhichun Xu